“Perhaps, when I have the time. But why come to me about the Christians in Alexandria? I am only a tribune, with little real authority.”

“You are the son of a Caesar and will one day rule ”

“You’re wrong there.” Constantine did not hide his irritation. “Emperor Diocletian has no intention of letting Caesars appoint their sons to succeed them.”

“But Caesar Galerius has already given his nephew great authority in the East. It is said here in Syria Palaestina that when Caesar Galerius becomes Augustus, Maximin Daia will be Caesar of this area and also of Egypt, so why shouldn’t your father appoint you in the West?”

“You were speaking of Egypt.” Constantine changed the subject abruptly. “What is it you want me to do?”

“The Emperor listens closely to you. If you were to ask that innocent people in Alexandria be spared, your request would carry much weight.”

Caesar Galerius

“And also give Caesar Galerius the opportunity he has been seeking to damage me with the Emperor,” Constantine pointed out. “Don’t you know that if it were left to him, he would destroy all you Christians?”

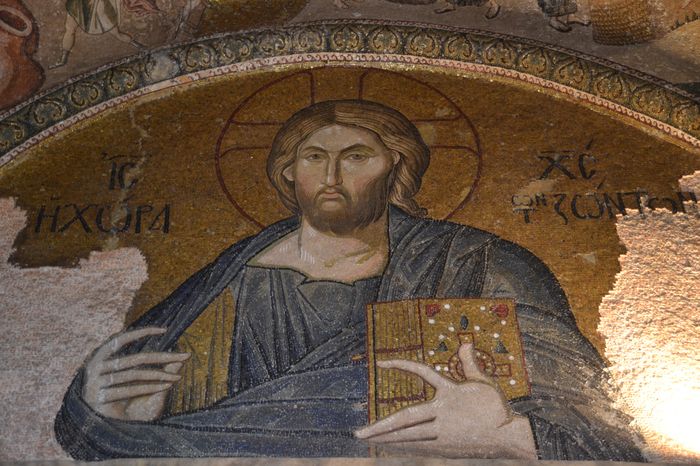

“I do know it,” Eusebius said soberly. “From all appearances we shall soon be persecuted again, as we were in the time of Nero, so I would save as many as I can. You see, Tribune Constantinus, persecutions come and go with the rulers who begin them, but the Church of Christ is eternal and neverending. Even if everyone in Alexandria is put to the sword, we will go on with the tasks Jesus set for us, when he was taken up into heaven after his resurrection. I ask only that, if the occasion arises, you do what you can to spare the innocent of Alexandria, whether Christian or pagan the same thing your father has done in Gaul and Britain.”

“I will do what I can,” Constantine promised. “But don’t expect much. The Emperor puts much store on pronouncements by soothsayers and oracles. If he has been told by them to make the streets of Alexandria flow with blood until it touches the knees of his horse, then I suspect he will do it.”

Constantine’s first view of Alexandria was exciting, coming as it did at night when the fires of the great lighthouse called the Pharos had already been lit and the mirrors behind them at the top of the great column of white stone reflected the rays of the fiery beacon far out to sea. Nowhere in the world, he knew, was there anything even remotely able to vie with the Pharos either in height or in grandeur. But his military instinct also reminded him that the great column was a considerable hazard to the Roman attack upon the city, since observers posted upon it constantly spied upon every activity in the Roman camp.

Read More about A great amphitheater and a palacecitadel