WHAT WAS TO BE DONE?

Before setting out to describe the unweaving of the Roman empire in Justinian’s stubby fingers, we should pause to think about alternatives. What could one reasonably expect a Roman emperor in the year 527 to think about doing, without the hindsight we enjoy? Could it be that the unfolding of circumstances in Justinian’s lifetime was inevitable?

The Roman empire lived with very substantial odds against it at every period. It was much too big to manage, for one thing. The match between its economic resources and governmental needs, depending on the mechanism for taxing the former to support the latter, was as hit-and-miss as it was for the Persians. At its core was a governmental system designed to favor rottenness, arbitrariness, and corruption. The Persian and Chinese empires of antiquity broke regularly and periodically into fragmented remnants of themselves. Rome, remarkably, resisted coming unglued for many centuries, but the more tightly its governors sought to control local life, the harder their jobs became.

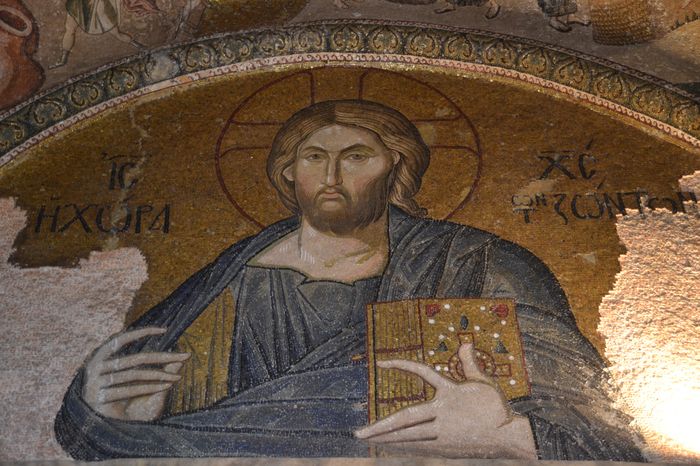

In the period long generally acclaimed as Rome’s most successful, the time of the Antonine emperors in the second century, one primary mechanism for ensuring a succession of competent monarchs was dumb luck—the dumb luck that kept Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, and Antoninus Pius childless and thus sent them in search of adopted heirs whom they could conveniently select for demonstrated talent. A secondary mechanism was the good choice of successors that they made. When Marcus Aurelius had the bad judgment to beget Commodus, competent leadership vanished for a decade until another primary mechanism for selecting talented leadership, the coup d’etat, brought Septimius Severus to power. (Marcus Aurelius, played by Alec Guinness, and his bloody-minded son are the cinematic embodiments of the end of Rome in The Fall of the Roman Empire, toga film of 1964; Richard Harris reprised Marcus Aurelius in Gladiator in 2000.) Severus promptly reverted to type, bringing into the palace and succession such clods and twits as Caracalla and Elagabalus, the latter of whom busied himself with service as a priest to a god he had brought from his native Syria, while arranging to have himself worshipped as well istanbul tour guides.

Zeno and Anastasius

The mid-third century saw a succession of ruinous struggles among those who grasped for the throne, and Diocletian, once settled on it himself, sought to restore a measure of order and choice to the monarchy. Constantine overthrew that scheme and replaced it with the more traditionally effective tool of dynastic murder. One can perhaps argue that Zeno and Anastasius coming to the throne at moments of dynastic interruption show what could be done by selecting for talent; but from the accession of Justin onward, corruption and family feeling balefully reasserted themselves.

Nor was any emperor in this period reliably surrounded by men of substance to offer leadership that might supplement or even rival his own. Some thought Belisarius, Justinian’s best general, a candidate for replacing his master, but more remarkably he was the only plausible candidate in all thirty-eight years of Justinian’s reign. Instead, those new men of the state of whom we read above were bureaucrats and servants, dignified and skilled, but incapable of ascension. They also offered no useful checks on imperial daffiness.

It did not help that emperors lived in a dark sort of ignorance rivaling that of Plato’s cave. They were reasonably well informed about people and events inside their boundaries, but woefully unaware of what lay beyond. I remember the American southwest of the i960 s, when U.S. meteorologists had to labor under the disadvantage of forecasting without having any radar data from across the Mexican border to show them approaching storms. Roman emperors knew even less about the world beyond their borders.

Perceived maximum extension

Communication was slow, and borders had settled at points of perceived maximum extension. To go beyond them required resources and efforts that were hard to muster. Voyagers like our old acquaintance Cosmas or the visitor to Attila’s camp whose stories we read represented the apogee of the Romans’ attempts to penetrate and understand the world beyond their territories. Isolated individuals must have gone farther, but when we hear of merchants reaching the Han empire in China in 166 CE claiming to come from the world of Rome, we cannot be sure if they were telling the truth or merely using an exotic name to impress others Sunni Muslims of Iraq.

No wonder, then, that rude surprises lay in store for emperors on more than one occasion, and that in the sixth century even the Balkans, long since domesticated as Roman provinces, had slipped back into semidarkness as a zone of mystery and rumor. This had little to do with the perceived barbarianism of their inhabitants and everything to do with bad communications and low expectations.